The Massacre of the Corbly Family

The following accounts are from: “Life and Times of Reverend John Corbly and Genealogy” written by Nannie L. Fordyce

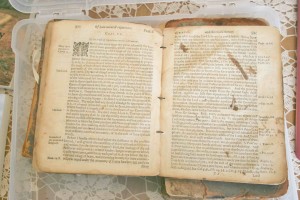

There are two versions of the Corbly massacre. One version was written by John Corbly to Reverend William Rogers1 of Philadelphia, three years after the massacre. The letter was written at the request of Mr. Rogers, to whom Corbly had related the story when he made a trip to Philadelphia to get medical aid for his daughters, Delilah and Elizabeth, who survived the massacre. The other was written nearly one hundred years later (1875) by L. K. Evans. Records now show Mr. Evans did not have correct information concerning the age of Priscilla and John Corbly, Jr., who he says were children of Elizabeth Tyler Corbly. John Corbly and second wife, Elizabeth Tyler, were married in 1773. Ohio records show Priscilla was born in 1762 (see Genealogy, page 63). According to his tombstone inscription, John Corbly, Jr., was born in 1768 (see Genealogy, page 63). These records show Priscilla and John Corbly, Jr., were children of the first wife, Abigail Bull Corbly, who died in the latter part of 1768. John Corbly, Jr., was fourteen years old at the time of the massacre, and not eleven, as stated by Mr. Evans. Conflicting statements are soon encountered if we try to include any of the first wife’s children in the story of the massacre.2

William Rogers’ request for a written account of the massacre concerns only the family of Elizabeth Tyler Corbly, and John Corbly in replying is writing undoubtedly only of the second wife and her five children, who were victims of the massacre.3

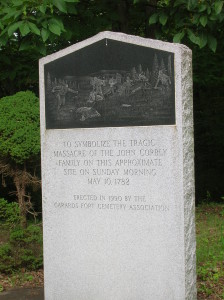

The massacre occurred on Sunday morning, May 10, 1782. A party of Indians was on “Indian Point,” an elevation of land from which they could see John Corbly’s cabin, the log meetinghouse which was located on the edge of the graveyard, and the fort which was about four hundred yards east of the meetinghouse. Because of a rise of ground the fort was out of view of the massacre, but it was within hearing distance, for the screams of the Corbly family were heard there and in a very few minutes men on horseback rushed out from the fort to give help

The Corbly family had left their home and were proceeding on their way to worship where Mr. Corbly was to preach, when it was discovered that the Bible, which he thought was in Mrs. Corbly’s care, had been left at home. He returned to get it and then followed his family, meditating upon the sermon he soon expected to preach.

The Indians descended the hill, crossed Whitely Creek, and filed up a ravine to the place, about forty-nine rods north of the present John Corbly Memorial Baptist Church, where the helpless family was massacred. The following is John Corbly’s story of the massacre, as written to his friend, the Reverend William Rogers, July 8, 1785.4

“On the second Sunday of May in the year 1782, being about to keep my appointment at one of the meeting houses, about a mile from my dwelling, I set out with my dear wife and five children for public worship. Not suspecting any danger, I walked behind with my Bible in hand, meditating. As I was thus employed, all of a sudden, I was greatly alarmed with the frightful shrieks of my dear wife before me. I immediately ran with all the speed I could, vainly hunting a club as I ran, till I got within forty rods of them; my poor wife seeing me, cried to me to make my escape; an Indian ran up to shoot me. Seeing the odds too great against me, I fled, and by doing so outran him. My wife had a sucking child in her arms; the little infant they killed and scalped. Then they struck my wife several times, but not getting her down, the Indian who aimed to shoot me ran to her. My little boy, an only son, about six years old, they sank a hatchet into his brain and thus dispatched him. A daughter besides the infant they killed and scalped. My oldest daughter who is yet alive was hid in a tree about twenty yards from where the rest were killed, and saw the whole proceedings. She seeing all the Indians go off, as she thought, got up and deliberately came out from the hollow tree; but one of them spying her, ran hastily up, knocked her down and scalped her; also her only surviving sister, one on whose head they did not leave more than an inch round, either flesh or skin, besides taking a piece of her skull. She and the before-mentioned one are miraculously preserved; though as you must think, I have had and still have a good deal of trouble besides anxiety about them; insomuch as I am, as to worldly circumstances, almost ruined. I am yet in hopes of seeing them cured; they still, blessed by God, retain their senses, notwithstanding the painful operations they have already had, and yet must pass through.”4

Reverend Corbly had hoped his wife and children might be taken prisoners and yet retrieved. This hope vanished, he became the victim of a temporary despair. His soul sickened within him. By the kind nursing of sympathizing friends he was cheered at the prospect that two of his daughters might yet survive.5

The following description of the family after the massacre is from Evans’ story:

“Margaret, his eldest daughter, described the scene of the massacre as witnessed by her when the killed and mangled were borne from the place of slaughter to the fort. She said it seemed only an incredibly short space of time from her hearing her stepmother scream till one of the fort people came riding in great haste, carrying the murdered woman dangling across the withers of the horse. The skirt of the dress, which was a black silk one, had been cut off close to the waist and she was frightfully mangled and smeared with gore. A few minutes later others came bearing the little ones, dead and dying and suffering.”

“Two of his daughters, Elizabeth and Delilah, gave sighs of returning life. The little boy, Isaiah, lived twenty-four hours. He revived enough to cry piteously and scream deliriously for the Indians to save his life, which Grandfather Corbly had been known to say was the severest trial of his life. Gladly would he have died to save his darling boy.”

“Elizabeth survived until twenty-one years of age. Sometimes she would seem to be entirely well, then the sore would suddenly reopen and endanger her life. She was said to be a very fascinating girl and was betrothed to Isaiah Morris. Preparations had been made for the nuptial occasion when very suddenly the wound broke afresh and in a few day she was a corpse.” (She always maintained that a white man had scalped her.)

“Delilah got well, lived to marry a Mr. Martin, and reared a large family somewhere in the great Miami valley.”

Delilah and her husband are buried in the Staunton Graveyard, near Troy, Ohio. Delilah’s family physician has given a description of her scalp wound which, he said, “extended over the crown of her head as wide as two hands. The hair grew thriftily around the edge of the scalp surface and she trained it to conceal the wound. At times it caused great pain. Notwithstanding the severity of her wound she lived to the age of 64 years, 7 months and was the mother of eight sons and two daughters.”6

Reverend Corbly does not mention the name of John Corbly, Jr., son of his first wife, in his letter to William Rogers. The traditional story of John Jr.’s, escape from the Indians has been handed down from generation to generation. John, Jr., accompanied by his dog, had probably preceded the family to the place of worship, and was somewhere near the scene of the massacre when his presence was observed by an Indian who gave chase as John ran in the direction of the fort. The following narration is from papers of the late Corbly Garard:

“Fortunately the boy’s faithful dog, a large one, was with him that morning and in his race for life also became an attacking party. So fiercely did the dog assail the Indian’s leg and impede his progress that the fleet-footed boy make his escape to the fort. This is the story of his escape so often related by this son who grew to manhood and who also became a Baptist minister.”

The lives of John Corbly and John, Jr., were no doubt saved by the quick action of the men in the fort who hastened on horseback to the scene of the massacre as soon as the first screams were heard. While some of the men who went out brought members of the Corbly family to the fort, others followed the savages as far as the Ohio River. When the Indians crossed into hostile territory, it was thought best not to pursue them further. This closes the story of the Corbly massacre which was one of the most brutal ever perpetrated in this region and of which Mr. Evans writes, “Viewed in all its bearings, it is unsurpassed in enormity by any in the annals of border life…. It is not an incident of traditionary fame merely, but is one that has long since passed into history and is as familiar to the readers of the States as almost any other historic event.”

After the Revolutionary War, with the exception of two short public services, contemporaneous with his religious work, John Corbly devoted all his time to the ministry.

1 William Rogers was pastor of the First Baptist Church in Philadelphia.

2 William J. Knight.

3 Ibid.

4 From True Stories of Pioneers, published by Lancaster, Pa., Publishing Co., 1830.

5 L. K. Evans, op. cit.

6 William J. Knight, Urbana, Ohio.